Roasting Parched Corn

Use these Native American “Parching Orders” to prep your own lightweight, high-energy backwoods snacks and rockahominy!

When the first European settlers arrived as colonists in my old stomping grounds along the New England coast, they nearly starved to death until they were taught to plant corn in the Indian fashion. Corn sustained the Plymouth colony in its early years, and it became the staple of the American backcountry for almost 400 years. Even when I was a kid, a breakfast of either Johnnycakes or fried cornmeal mush was commonplace in the more rural areas of New England.

Corn was used in a variety of forms on the American frontier, but for life on the trail, the most useful form of corn was parched corn. That is as true today as it was in the eighteenth century. I would rather have a bag of parched corn with me on a hike or campout than granola or trail mix. Parched corn keeps well, and it has a great flavor…lots of corn flavor, but with a nutty overlay. As an added benefit, the longer you chew it, the more flavor it releases.

There are basically two ways of starting the process of parching corn, and each method yields a slightly different product. Classic parched corn starts with shelled corn, which are the dried corn kernels after they have been removed from the cob. If you grow your own corn, this is the way to go.

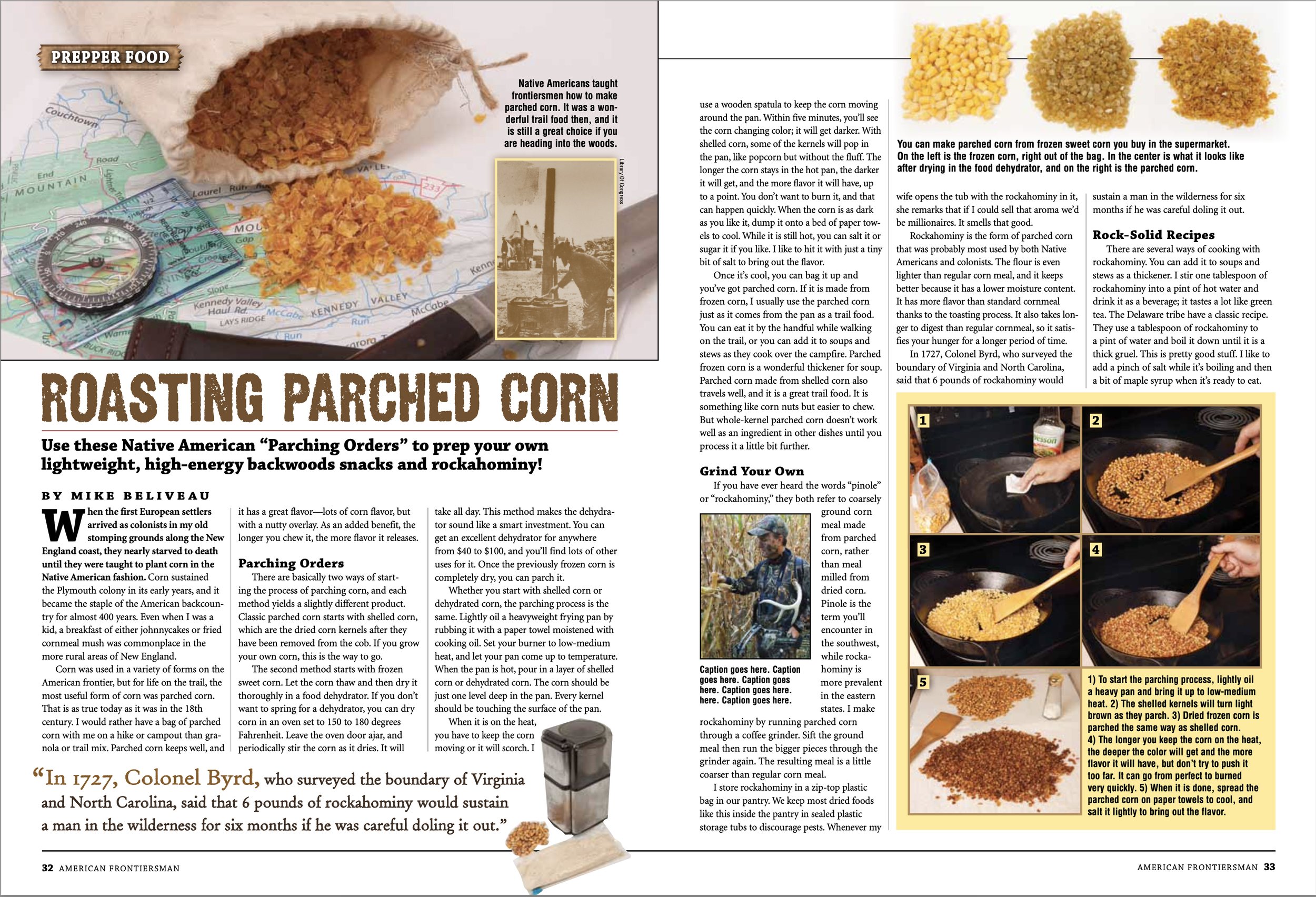

The second method starts with frozen sweet corn. Let the corn thaw and then dry it thoroughly in a food dehydrator. If you don’t want to spring for a dehydrator, you can dry corn in an oven set to 150 to 180 degrees. Leave the oven door ajar, and periodically stir the corn as it dries. It will take all day. Which makes the dehydrator sound like a smart investment. You can get an excellent dehydrator for anywhere from $40 to $100, and you’ll find lots of other uses for it. Once the previously frozen corn is completely dry, you can parch it.

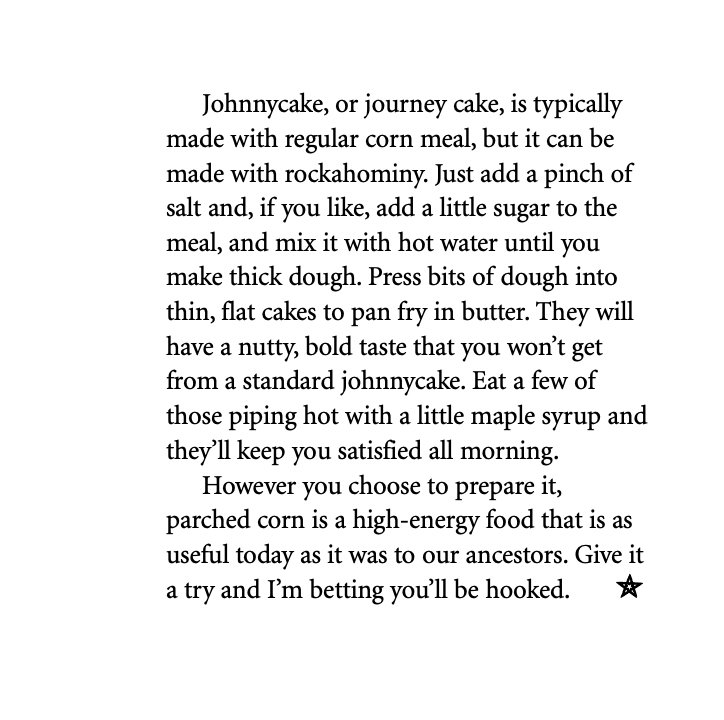

Whether you start with shelled corn, or dehydrated corn, the parching process is the same. Lightly oil a heavy weight frying pan by rubbing it with a paper towel moistened with cooking oil. Set your burner to low-medium heat, and let your pan come up to temperature. When the pan is hot, pour in a layer of shelled corn or dehydrated corn. The corn should be just one level deep in the pan. Every kernel should be touching the surface of the pan.

When it is on the heat, you have to keep the corn moving or it will scorch. I use a wooden spatula to keep the corn moving around the pan. Within five minutes you’ll see the corn changing color. It will get darker. With shelled corn, some of the kernels will pop in the pan, like popcorn, but without the fluff. The longer the corn stays in the hot pan, the darker it will get, and the more flavor it will have…up to a point. You don’t want to burn it, and that can happen quickly. When the corn is as dark as you like it, dump it onto a bed of paper towels to cool. While it is still hot you can salt it or sugar it, if you like. I like to hit it with just a tiny bit of salt to bring out the flavor.

Once it’s cool, you can bag it up and you’ve got parched corn. If it is made from frozen corn, I usually use the parched corn just as it comes from the pan as a trail food. You can eat it by the handful while walking on the trail, or you can add it to soups and stews as they cook over the campfire. Parched frozen corn is a wonderful thickener for soup. Parched corn made from shelled corn also travels well, and it is a great trail food. It is something like corn nuts, but easier to chew. But whole kernel parched corn doesn’t work well as an ingredient in other dishes, until you process it a little bit further.

If you have ever heard the words “pinole” or “rockahominy”, they both refer to coarse ground corn meal made from parched corn, rather than meal milled from dried corn into standard corn meal. Pinole is the term you’ll encounter in the southwest, while rockahominy is more prevalent in the eastern states. I make rockahominy by running parched corn through a coffee grinder. Sift the ground meal, and run the bigger pieces through the grinder again. The resulting meal is a little coarser than regular corn meal.

I store rockaharmony in a zip top plastic bag in our pantry. We keep most dried foods like this inside the pantry in sealed plastic storage tubs to discourage pests. Whenever Mary Pat opens the tub with the rockahominy in it, she remarks that if I could sell that aroma, we’d be millionaires. It smells that good.

Rockahominy is the form of parched corn that was probably most used by both Native Americans and colonists. The flour is even lighter than regular corn meal, and it keeps better because it has lower moisture content. It has more flavor than standard cornmeal, thanks to the toasting it has undergone. It also takes longer to digest than regular cornmeal, so it satisfies your hunger for a longer period of time.

In 1727, Colonel Byrd, who surveyed the boundary of Virginia and North Carolina, said that six pounds of rockahominy would sustain a man in the wilderness for six months, if he was careful doling it out.

There are several ways of cooking with rockahominy. You can add it to soups and stews as a thickener. I stir one tablespoon of rockahominy into a pint of hot water, and drink it as a beverage. It tastes a lot like green tea. The Delaware Indians have a classsic recipe. They use a tablespoon of rockahominy to a pint of water and boil down it until it is a thick gruel. This is pretty good stuff. I like to add a pinch of salt while it is boiling and then a bit of maple syrup when it is ready to eat.

Johnnycake, or journey cake, is typically made with regular corn meal, but it can be made with rockahominy. Just add a pinch of salt, and, if you like, add a little sugar to the meal, and mix it with hot water until you make thick dough. Pat small balls of the dough into thin, flat cakes and fry them in butter. They will have a nutty, bold taste that you won’t get from a standard Johnnycake. Eat a few of those, piping hot with a little maple syrup, and they’ll keep you satisfied all morning.

However you choose to prepare it, parched corn is a high-energy food that is as useful today as it was to our ancestors. Give it a try, and I’m betting you’ll be hooked on it.