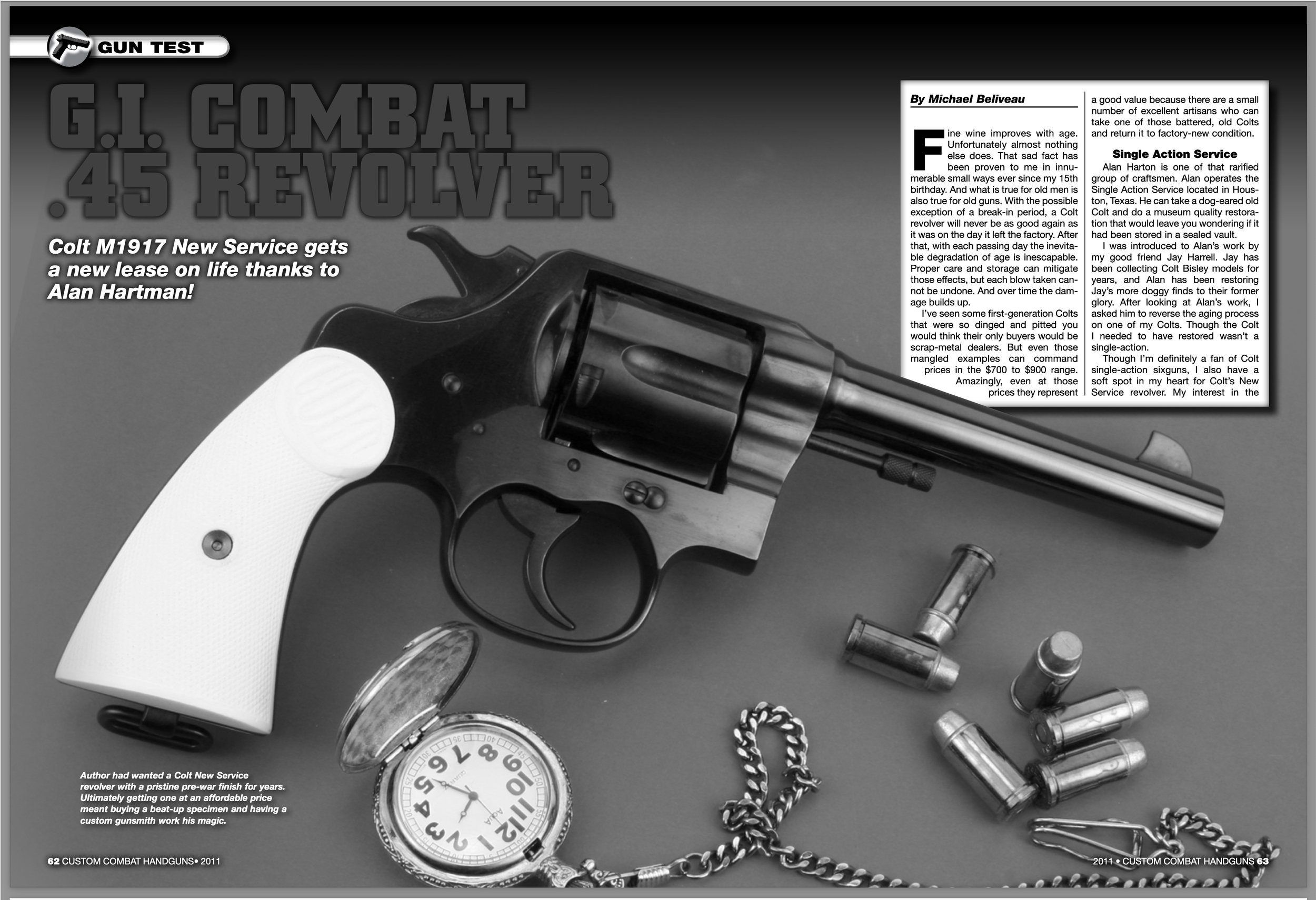

GI Combat .45 Revolver

Colt’s Model 1917 get rejuvenated by Alan Harton.

Fine wine improves with age. Unfortunately, almost nothing else does. That sad fact has been proven to me in innumerable small ways ever since my fiftieth birthday. And what is true for old men is also true for old guns. With the possible exception of a break-in period, a Colt revolver will never be as good again as it was on the day it left the factory. After that, with each passing day the inevitable degradation of age is inescapable. Proper care and storage can mitigate those effects, but each blow taken cannot be undone. And over time the damage builds up.

I’ve seen some first generation Colts that were so dinged and pitted they looked as if they had been run through a tumbler filled with particularly jagged rocks. But even those mangled examples can command prices in the $700 to $900 range. And, amazingly, at that price they represent a good value because there are a small number of excellent artisans who can take one of those battered, tired old Colts and return it to factory new condition.

Alan Harton is one of that rarified group of craftsmen. Alan operates the Single Action Service in Houston, Texas. He can take a dog-eared old Colt and do a museum quality restoration that would leave you wondering if it had been stored in a sealed vault since 1873.

I was introduced to Alan’s work by my good friend Jay Harrell; better known in cowboy action circles as Roughshod. Jay has been collecting Colt Bisley models for years, and Alan has been restoring Jay’s more doggy finds to their former glory. I was impressed with Alan’s work on Jay’s Colts, so I started using him for my own gunsmithing needs. Admittedly my needs are more mundane. For me Alan has done caliber conversions, action jobs and the like. And his work is excellent. But I wanted to take the opportunity to showcase what he does best, which is museum quality restorations of old, abused sixguns.

It’s embarrassing for me to admit that even at this advanced age I haven’t made my fortune yet. Therefore I don’t have a collection of first generation Colt Single Action Armies to use for this article. But even B-list gun scribes of modest means can have a first generation Colt of a certain type without emptying the 401K.

I have always had a yen for a Colt New Service revolver. As a high school kid in the late 60’s and early ‘70s I was a big fan of COL Charles Askins. I thought he was the real deal, and since he liked the Colt New Service revolver, naturally I liked ‘em too. I’d never shot one of course, but that didn’t stop me from liking them all the same.

I was in my 30s before I actually got to shoot a New Service. Intellectually, I knew they were big guns, but I was unprepared for long a the reach was to the trigger. I figured Askins must have had hands like Shaquile O’Neil’s to be able to comfortably shoot this beast in double action mode. I still liked the New Service as a concept, but as a practical sidearm…well let’s say that my ardor had cooled.

That changed a couple of years ago when a friend of mine bought a Colt 1917, which is a New Service variant originally built for use in World War I when 1911 autos couldn’t be built fast enough to meet the needs of the wartime army. My friend’s 1917 had been equipped with a set of Tyler T-Grips. This adapter gave an entirely different geometry to the 1917’s grip. Now I could reach the trigger easily for controlled double action shooting, and that long, smooth pre-war action was a joy to shoot. The fact that 1917s are chambered for the .45 ACP, which is my favorite defensive handgun cartridge, just made me want one more. I was hooked. I didn’t just want one…I needed one.

Being hooked on guns is a lot like being hooked on crack; only more expensive. Like with any addiction, admitting you have a problem is the first step to a cure, and I had a problem. I wanted a Colt 1917 in Colt’s high quality, pre-war civilian finish, and I didn’t want to spend a lot of money to get it. Finding reasonably priced Colt 1917 revolvers isn’t that tough. Colt made over xxx,xxx of them, but finding a pristine specimen is a lot harder.

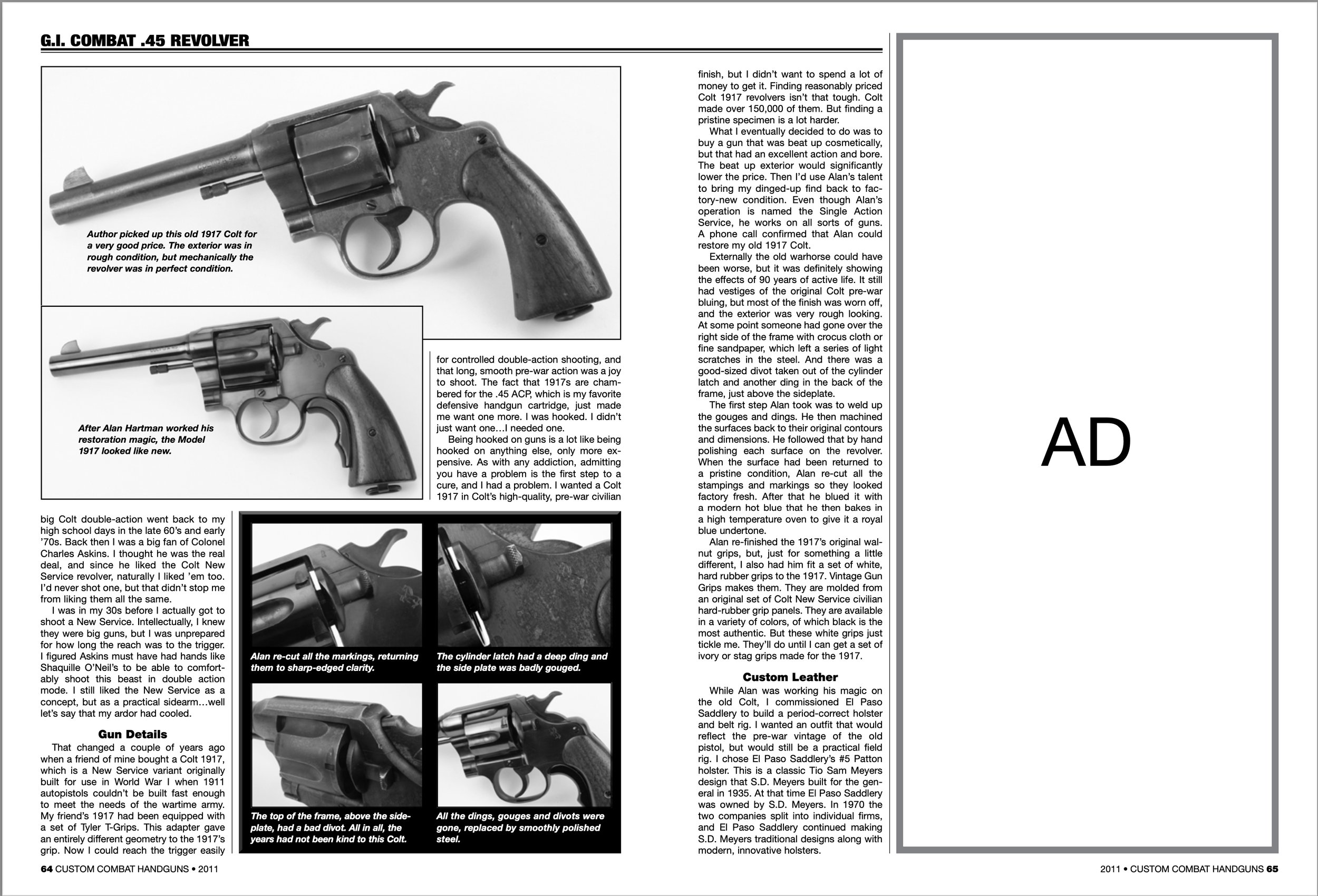

Eventually I decided to get one in excellent mechanical shape, and have the exterior restored; which is where Alan Harton comes in. Even though his operation is named the Single Action Service, Alan works on all sorts of guns. His specialty is doing museum quality restorations. I sent him some pictures of my 1917, and, after looking them over he told me to send the revolver in.

Externally my 1917 could have been worse, but it was definitely showing the effects of 90 years of active life. It still had vestiges of the original Colt pre-war bluing, but most of the finish was worn off and the exterior was very rough looking. At some point someone had gone over the right side of the frame with crocus cloth or fine sandpaper, which left a series of light scratches in the steel. And there was a good sized divot taken out of the cylinder latch and another ding in the back of the frame, just above the side plate.

The first step Alan took was to weld up the gouges and dings, and then machine the surfaces back to their original contours and dimensions. Then he carefully hand polished each surface on the revolver. When the surface had been returned to a pristine condition, Alan re-cut all the stampings and markings so they looked factory fresh.

Alan carefully polished the gun to a mirror finish before blueing it with a deep lustrous finish.

When he was done with it, the old warhorse was re-born, and it is ready for another century of service.