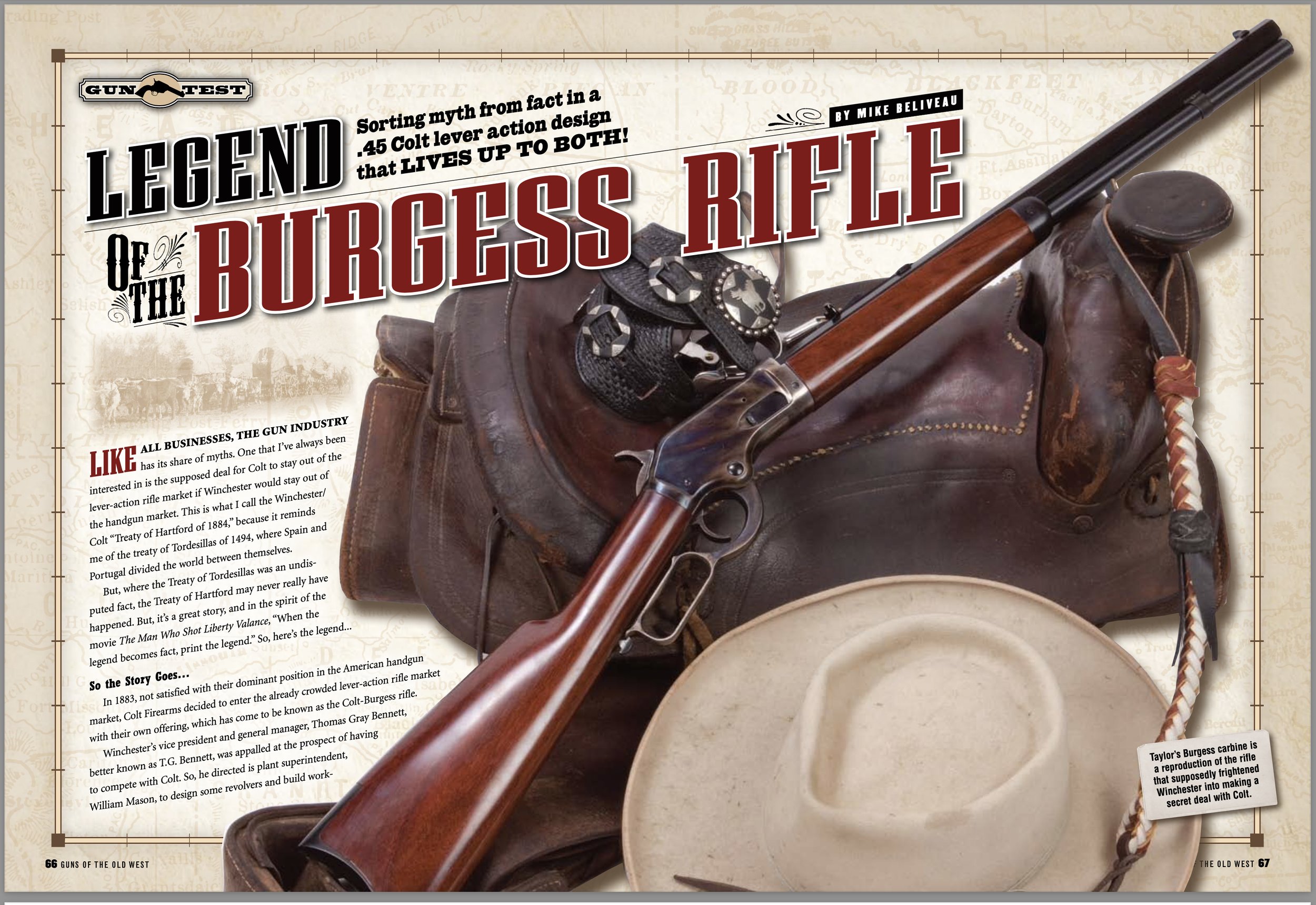

Colt’s Burgess Rifle - Uberti Replica

Like all businesses, the gun industry has its share of myths. One that I’ve always been interested in is the supposed deal for Colt to stay out of the lever action rifle market if Winchester would stay out of the handgun market. This is what I call the Winchester/Colt treaty of Hartford of 1884 because it reminds me of the treaty of Tordesillas of 1494, where Spain and Portugal divided the world between themselves.

But, where the treaty of Tordesillas was an undisputed fact, the treaty of Hartford may never really have happened. But, it’s a great story, and in the spirit of the movie “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence”; “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” So, here’s the legend.

In 1883, not satisfied with their dominant position in the American handgun market, Colt Firearms decided to enter the already crowded lever action rifle market with their own offering, which has come to be known as the Colt-Burgess rifle.

Winchester’s vice president and general manager, Thomas Gray Bennett, better known as T.G. Bennett, was appalled at the prospect of having to compete with Colt. So, he directed is plant superintendent, William Mason, to design some revolvers and build working prototypes. With the most promising design in hand, Bennett travelled from New Haven to Hartford for a friendly meeting with his opposite number at Colt.

During the course of that meeting, Bennett produced he Mason revolver and innocently asked if Colt’s president would be so kind to look it over, and give him an honest opinion of its viability in the marketplace. Bennett said he’d value the opinion of Colt’s president due to his superior knowledge of the cost of handgun manufacture, and of the interests of the handgun-buying marketplace.

As the story goes, when the president of Colt saw that William Mason revolver, his blood ran cold. He knew it was a good design. And if, Winchester threw its marketing muscle behind it, Colt could be in for a real fight to hold on to its market share. So he proposed that they break for lunch to give his accountants some time to work up some cost figures relative to starting up a handgun line. Bennett thought that would be a capital idea. And, while they were at it, Bennett wondered if it might not be possible to see Colt’s figures on the Burgess rifle as well.

After lunch the two executives went over the figures. Colt’s figures showed that starting a handgun line would be ruinously expensive for Winchester. And, the president of Colt was shocked to learn that they were barely making any money at all off the Burgess rifle. He announced on the spot that Colt would close the Burgess line immediately. T.G. Bennett, nodded his head ruefully and said he guessed it would be better if Winchester stayed out of the pistol market too.

What a great story! But did it ever happen? Your guess is as good as mine, but my guess is, No. And here’s why. First of all Winchester was already competing with the likes of Marlin, Kennedy, Whitney and Evans. In the bare-knuckled fight that was nineteenth century capitalism, Winchester was more than holding its own. If anybody scared them it was Marlin, not Colt. Secondly, the Colt Burgess wasn’t exactly setting the world on fire. Colt sold less than 6,500 of these rifles over the entire production run. In 1883 alone Winchester sold almost 35,000 units of their Model 1873 lever gun, not to mention the 1876 and other models. So, it is pretty doubtful that T.G. Bennett was losing sleep at night because of the Colt-Burgess. And, finally, if Colt really did cut a deal to get out of the lever gun market, they were pretty dilatory about it. They kept producing the Burgess until 1887.

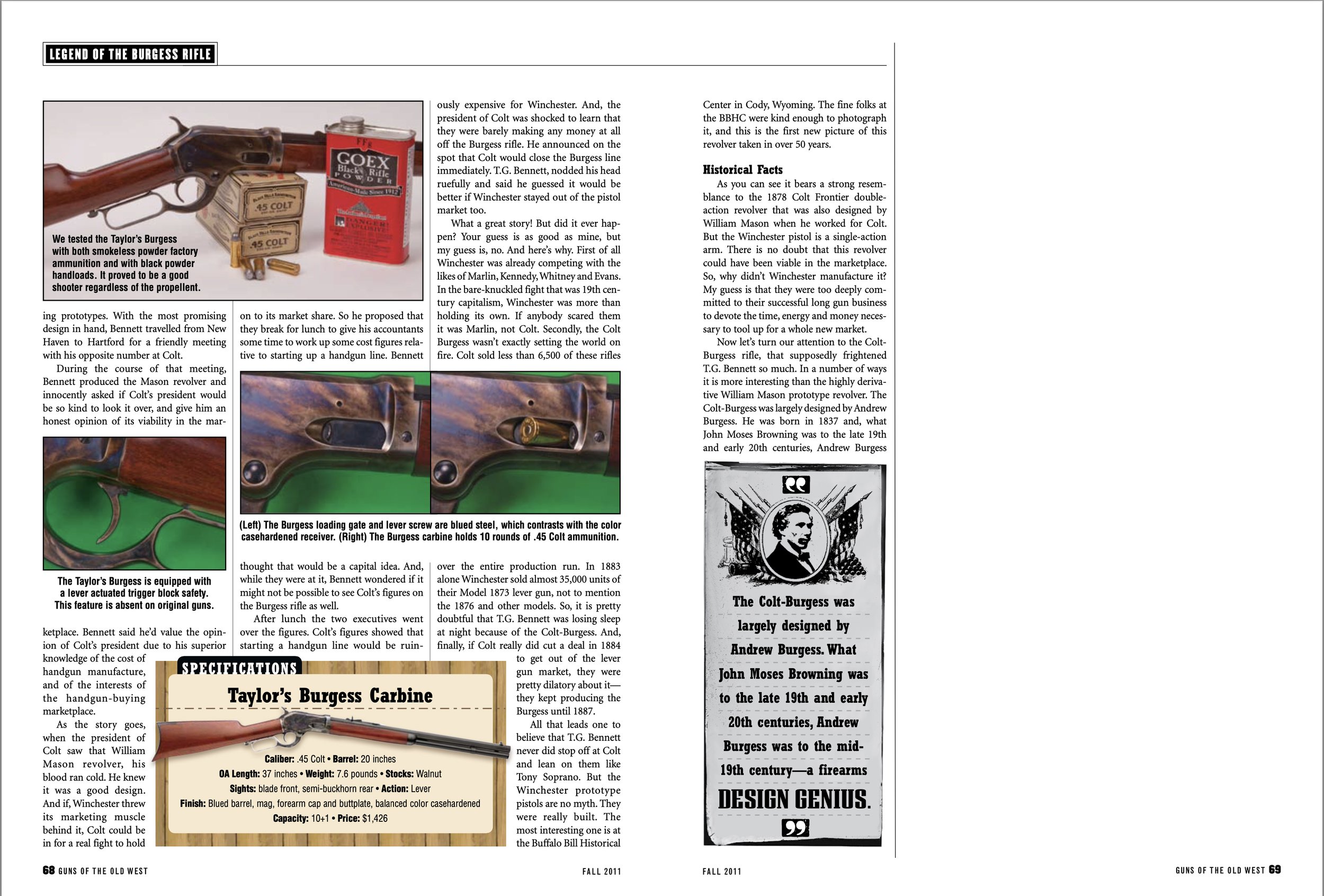

All that leads me to believe that T.G. Bennett never did stop off at Colt and lean on them like Tony Soprano. But the Winchester prototype pistols are no myth. They were really built. The most interesting one is at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming. The fine folks at the BBHC were kind enough to photograph it for this article. This is the first new picture of this revolver taken in over 50 years.

As you can see it bears a strong resemblance to the 1878 Colt Frontier double action revolver that was also designed by William Mason when he worked for Colt. But the Winchester pistol is a single action arm. There is no doubt that this revolver could have been viable in the marketplace. So, why didn’t Winchester manufacture it? My guess is that they were too deeply committed to their successful long gun business to devote the time, energy and money necessary to tool up for a whole new market.

Now let’s turn our attention to the Colt-Burgess rifle, that supposedly frightened T.G. Bennett so much. In a number of ways it is more interesting than the highly derivative William Mason prototype revolver. The Colt-Burgess was largely designed by Andrew Burgess. He was born in 1837 and, what John Moses Browning was to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Andrew Burgess was to the mid-nineteenth century. He was a firearms design genius.

A lot of people think that Winchester’s model 1886 rifle, designed by John Browning, was the first lever action chambered for the .45-70 government cartridge. It was not. Andrew Burgess was there first with the model 1878 Whitney-Burgess long-range rifle. Over his life Burgess acquired over 500 firearms patents. Many of them are still in use in production arms today.

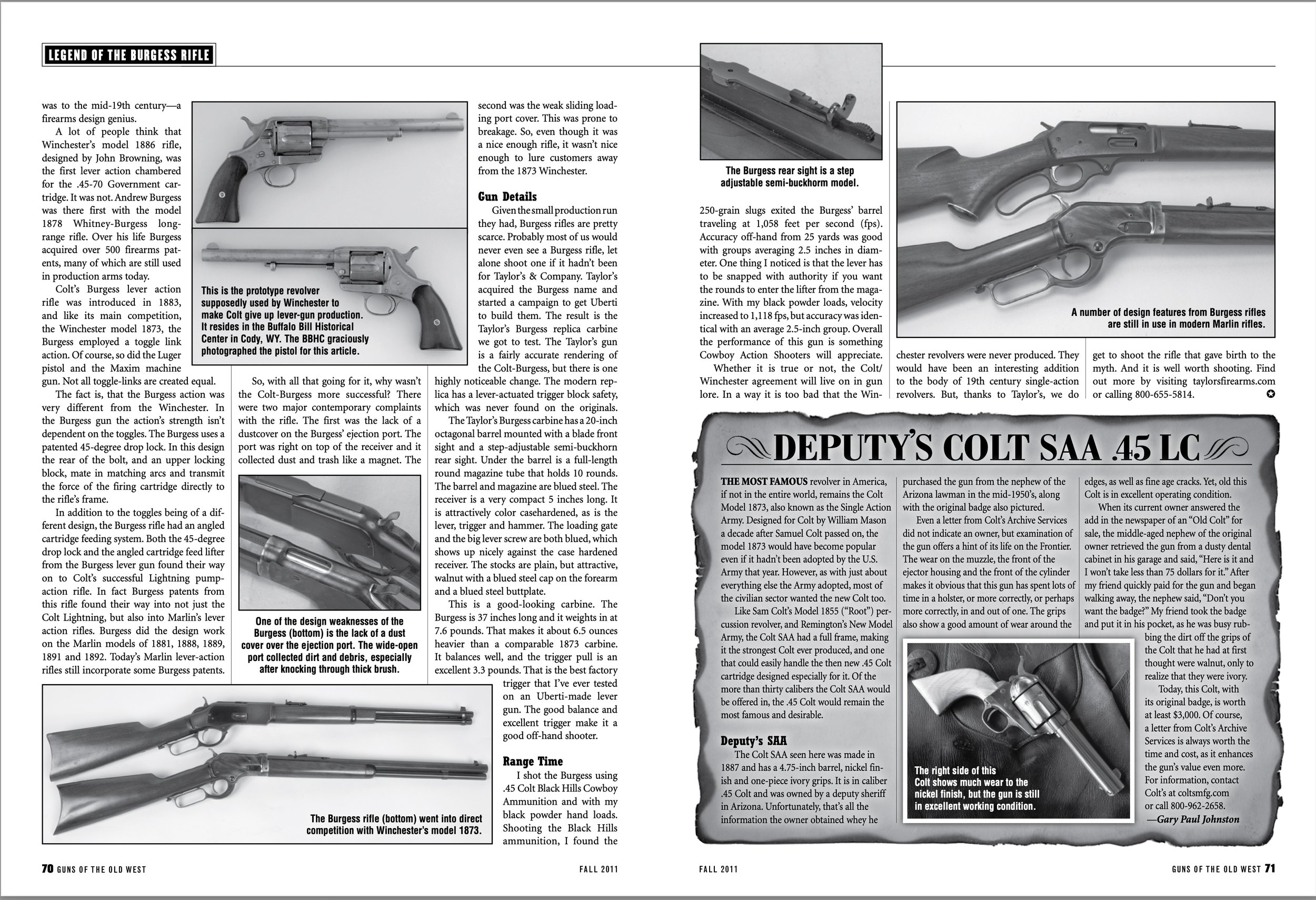

Colt’s Burgess lever action rifle was introduced in 1883, and like its main competition, the Winchester model 1873, the Burgess employed a toggle link action. Of course, so did the Luger pistol and the Maxim machine gun. Not all toggle-links are created equal.

The fact is, that the Burgess action was very different from the Winchester. In the Burgess gun the action’s strength isn’t dependent on the toggles. The Burgess uses a patented 45-degree drop lock. In this design the rear of the bolt, and an upper locking block, mate in matching arcs and transmit the force of the firing cartridge directly to the rifle’s frame.

In addition to the toggles being of a different design, the Burgess rifle had an angled cartridge feeding system. Both the 45-degree drop lock and the angled cartridge feed lifter from the Burgess lever gun found their way on to Colt’s successful Lightning pump-action rifle. In fact Burgess patents from this rifle found their way into not just the Colt Lightning, but also into Marlin’s lever action rifles. Burgess did the design work on the Marlin models of 1881, 1888, 1889, 1891 and 1892. Today’s Marlin lever action rifles still incorporate some Burgess patents.

So, with all that going for it, why wasn’t the Colt-Burgess more successful? There were two major contemporary complaints with the rifle. The first was the lack of a dust cover on the Burgess’ ejection port. The port was right on top of the receiver and it collected dust and trash like a magnet. The second was the weak sliding loading port cover. This was prone to breakage. So, even though it was a nice enough rifle, it wasn’t nice enough to lure customers away from the 1873 Winchester.

Given the small production run they had, Burgess rifles are pretty scarce. Probably most of us would never even see a Burgess rifle, let alone shoot one if it hadn’t been for Taylor’s & Company. Taylor’s acquired the Burgess name and started a campaign to get Uberti to build them. The result is the Taylor’s Burgess replica carbine we got to test. The Taylor’s gun is a fairly accurate rendering of the Colt-Burgess, but there is one highly noticeable change. The modern replica has a lever-actuated trigger block safety, which was never found on the originals.

The Taylor’s Burgess carbine has a 20-inch octagonal barrel mounted with a blade front sight and a step-adjustable semi-buckhorn rear sight. Under the barrel is a full length, round magazine tube that holds 10 rounds. The barrel and magazine are blued steel. The receiver is a very compact five inches long. It is attractively color case hardened, as is the lever, trigger and hammer. The Loading gate and the big lever screw are both blued, which shows up nicely against the case hardened receiver. The stocks are plain, but attractive, walnut with a blued steel cap on the forearm and a blued steel butt plate.

This is a good looking carbine. The Burgess is 37 inches long and it weights in at 7.6 pounds. That makes it about six and a half ounces heavier than a comparable 1873 carbine. It balances well, and the trigger pull is an excellent three pounds three ounces. That is the best factory trigger that I’ve ever tested on an Uberti-made lever gun. The good balance and excellent trigger make it a good off hand shooter. That was borne out at the range.

We shot the Burgess using .45 Colt Black Hills Cowboy Ammunition and with my black powder hand loads. Shooting the Black Hills ammo, we found the 250-grain slugs exited the Burgess’ barrel traveling at 1,058 feet per second. Accuracy off-hand from 25 yards was good with groups averaging two and a half inches in diameter. One thing we noticed is that the lever has to be snapped with authority if you want the rounds to enter the lifter from the magazine. With my black powder loads velocity increased to 1,118 feet per second, but accuracy was identical with an average two and a half inch group. Overall the performance of this gun is something cowboy action shooters will appreciate.

Whether it is true or not, the Colt Winchester agreement will live on in gun lore. In a way it is too bad that the Winchester revolvers were never produced. They would have been an interesting addition to the body of nineteenth century single action revolvers. But, thanks to Taylor’s, we do get to shoot the rifle that gave birth to the myth. And it is well worth shooting.

Specifications:

Taylor’s & Co. Burgess Carbine

Caliber: .45 Colt

Barrel: 20 inches

OA Length: 37 inches

Weight: 7 lbs 9 oz

Finish: Blued barrel, magazine, forearm cap and butt plate. Balanced color case hardened

Stocks: Walnut, two-piece

Sights: blade front, semi-buckhorn rear

Capacity: 10 rounds

Points of contact

Taylor’s & Company, Inc.

304 Lenoir Drive

Winchester, VA 22603

800-655-5814